3D Art

Abstraction & Non-Objective Art

"Simplicity is complexity resolved." - Constantin Brancusi

"The great artist is the simplifier." - Vincent van Gogh

"The art of art, the glory of expression and the sunshine of the light of letters, is simplicity." - Walt Whitman

Abstraction Theory

As an artist and instructor, I've been asked numerous times, "What does it take to appreciate abstract art?" Others have confided that they "don't like abstract art because it's too difficult to understand." I usually offer encouragement by suggesting a way to think about this fascinating art-form. My approach is relatively simple and begins by examining the difference between abstraction and non-objective art.

Often, abstraction is confused with non-objective art. Abstraction (from the Latin root, "tract", to pull, and the prefix "ab", away) is the process of simplification: the pulling away of superfluous and irrelevant information until the artist arrives at a point wherein only the MOST IMPORTANT aspect of a thing remains. Removing the unwanted elements of a subject leads, invariably, to a simplified form that's quicker to behold and therefore easier to read. The viewer, unburdened with the distraction of unnecessary details, is given a figurative "lens" through which she might better examine and appreciate certain aspects of the phenomenal world. This is the true gift of abstraction.

The Romanian artist, Constantin Brancusi, was a master of abstraction. He reduced the number of irrelevant features on his marble and bronze sculptures until as few as one or two characteristics remained.

The work titled, Bird in Space depicts no feathers, no wings, no beak, no talons, yet it beautifully encapsulates the graceful arc of a raptor's body as it pierces the sky, defying gravity on its heavenward trajectory. Brancusi could not have pulled away a single detail more, without the form losing all resemblance to a bird in flight.

Another of his sculptures, (cast in bronze and polished to a brilliant finish) has a small, counter-curving ridge erupting from the bottom of an oval plane, which intersects a larger, egg-shaped volume. This small protuberance is the only feature that provides a clue as to the subject of the work: it's an abstraction of the wide-open mouth of an infant, frozen in mid-scream, with its lower lip curving downward in the unmistakable gesture of anguish and emotional distress.

I've asked my students to identify the source of inspiration for this sculpture. Few of them could guess correctly, but everyone saw the resemblance when I told them that the title is, Crying Muse (or new-born II). Even-though the work has been highly abstracted, it remains connected to a familiar object: that of a crying new-born. In fact, it's hard NOT to see the resemblance once you know the title.

Non-Objective Subject Matter

"My paintings are certainly non-objective; they're just horizontal lines." - Agnes Martin

There's an alternate way to view abstraction (as a verb): as a reversal of the process that I've described above. Instead of subtracting characteristics from a subject until we arrive at something that's essential, we can look to the world around us and extract something that we consider important, surprizing or interesting. In the end, it's really the same process but oriented in different directions: 1) from a physical object or specific observation OUTWARD until we arrive at a generalized representation, such as the abstracted theory or the abstract work of art; 2) from a broader observation INWARD until we arrive at a more specific solution, but one that does NOT necessarily begin with a corresponding object in the physical world.

In other words, a general and broadly applicable observation like, for instance, the need to define a quantity of something, may lead to the creation of symbols in the form of Roman or Hindu-Arabic numerals: the idea leads to an object instead of an object leading to an idea. In this sense, a symbolic representation (like Ⅴ or the number 5) begins mostly, if not entirely in the mind, necessitating (in the sphere of visual art) the use of a different term that implies the artwork does not lead back to an originating object: non-objective.

Non-objectivity implies that NO OBJECT is discernible within the subject matter (i.e., the subject cannot be traced back to a physical thing). Many elements may be present - shape, value, colour, line, mass, texture - but all of these things exist WITHOUT reference to a recognizable person, place or thing.

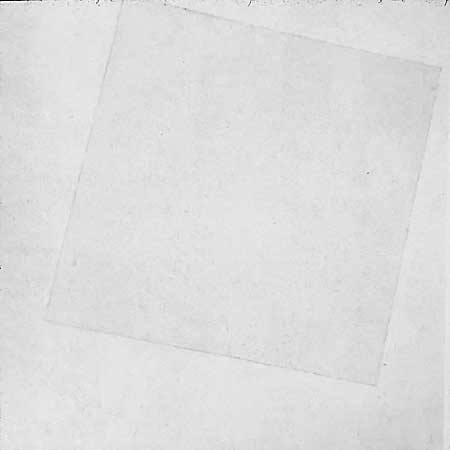

A non-objective painting, made by the Russian artist Kazemir Malevich and titled, White on White, explores the aesthetic qualities of geometric forms by depicting a white square against a white background. The supreme beauty of geometry is a tenet of Suprematism, an art movement from the early twentieth century.

One could argue that a square is a "thing", so why not call it abstract, like Bird in Space? A bird is a thing, without doubt: we can see, hear, smell and touch it. A square, on the other hand, EXISTS ONLY as a well-defined set of mathematical rules: a concept within a vast, Platonic universe of ideas. Many things may be square in appearance - signs, windows, walls, furniture - but they are NOT SQUARES in-and-of-themselves. A square is not an object but rather, an idea.

The line that separates abstraction from non-objectivity, thing from idea, may be more a matter of context than of consistent definitions. Without knowledge of Brancusi's intentions or the information provided by a title, a viewer might assess his sculpture as having NO discernible object in its subject matter. She might therefore conclude that Bird in Space is a non-objective artwork.

She would not be wrong, because in this instance her understanding of the artwork is incomplete: to her, it IS a non-objective artwork. Abstract artworks can sometimes be misidentified as being non-objective, but a non-objective artwork should never be called "abstract", because nothing (no-thing) has been abstracted in its making.

Whether it be abstract or non-objective, these deceivingly simple artworks are powerful devices, allowing us to see a world that would otherwise be hidden from view.

Returning to the question, "What does it take to understand abstract art?", the answer is: it takes curiosity and observation. When the viewer makes an effort to learn about the artist's intention (asking, "What's the subject matter?"), she's more likely to recognize the work's most important characteristics. This is where understanding begins.

Medium Specificity

"It would follow that 'significant form' was form behind which we catch a sense of ultimate reality." - Clive Bell

"Art is significant deformity." - Roger Fry

"Content is to be dissolved so completely into form that the work of art or literature cannot be reduced in whole or in part to anything not itself." - Clement Greenberg

In 1914, Clive Bell (a British, aesthetics philosopher) wrote about the transcendent beauty and supreme power of "Significant Form" in art. His contemporary, Roger Fry (a British artist and fellow member of the Bloomsbury Group) wrote about the importance of the Formal Elements in Modern Art. Sometime later, the American art critic and theorist, Clement Greenberg (active in the mid-twentieth century) popularized the notion of medium specificity: essentially, the categorization of art-making into narrow, medium-specific regions of activity. Although it's a gross simplification, it appears that Greenberg was familiar with Fry's writing, who in turn was inspired by Bell.

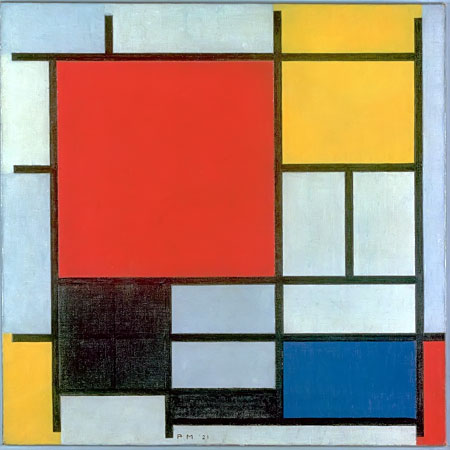

Let's use painting as an example, to see how medium-specificity works... Painting is an activity wherein pigment is applied to a two-dimensional surface. If the only thing essential to a painting is the application of paint to a surface, then depicting illusory space and naturalistic forms are incidental and completely unnecessary; therefore, most of a painter's efforts (from a medium-specific stance) should, ideally, be directed toward applying paint to a surface and NOT the creation of illusory space inhabited by illusory people and illusory objects.

Greenberg (among others) insisted that a well-defined territory of material-specific activity is extremely useful because it informs and guides the artist's choices while making an artwork. Implicit, is the notion that allowing ones materials to drive the creative process is inherently more honest than traditional forms of depiction. In other words, NO SPACE exists beyond the picture plane, so why pretend that it does by painting naturalistically? (Click here to read Greenberg's writing: Art and Culture: Critical Essays.)

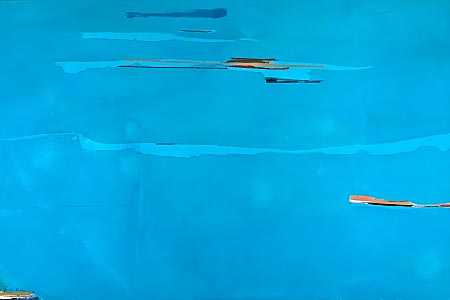

It seems self-evident, that adhering to a well-defined set of guidelines (ideals) could provide direction and clarity for the artist. As an example: the medium-specific approach of Colour Field painting necessitates that a work be primarily (or exclusively) about the effects of colour on a two-dimensional surface. Line, shape, texture, value and mass were irrelevant to many Colour Field painters, so they pulled away those elements from the subject until they arrived at a composition that's sufficient and necessary to make the meaning clear. The result can be extreme abstraction, like the paintings of Helen Frankenthalar, or non-objectivity, like the paintings of Mark Rothko (both of whom produced Colour Field paintings).

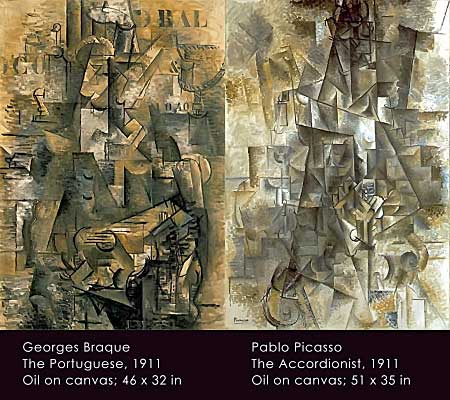

Whenever a specific formal element or an idea is privileged above all others, a preference for a certain kind of imagery (a "style") will PRECEDE (or supplant) any mimetic considerations, which is why it's almost impossible to find a Colour Field painting with depth (illusory space). By declaring allegiance to a specific material or a narrow range of processes, the artist discovers some direction and motivation for a time, but it's purchased at a cost: that is, the freedom to move beyond the requisite characteristics that one expects of a selected medium or an artistic style. This is why it's sometimes hard to differentiate the works of artists who shared similar ideals, such as the Cubist works of Braque and Picasso, both of whom took abstraction to the opposite extreme: where instead of simplifying an object, they made it MORE COMPLEX by adding information that suggests multiple, simultaneous views (for a wonderful explanation of how to read a highly-abstracted painting by Picasso, follow this link to How To Understand A Picasso, by The Nerdwriter).

Throughout the twentieth century, many such ideals provided crucial momentum for progress in the Visual Arts, leading to ever-more daring experiments with abstraction (remember, abstraction was a relatively new approach for artists in the early part of the twentieth century). Over and over again, art movements arose to challenge the declared values of the previous movements (a sort of "call & response" phenomena): Impressionism calls forth Post-Impressionism, which calls forth Fauvism, which calls forth Expressionism, which calls forth Abstract Expressionism, and so on. It's sort of like a rebellious youth who does the opposite of whatever her parents ask, only to become a parent herself one day, giving birth to a rebellious child of her own.

There may be a danger of becoming too dogmatic about such things, thereby creating artworks that never transcend beyond the very narrow appeal of their physical properties. Moreover, when art-making is confined to only the most severe kind of formalism (one that EXCLUDES ALL non-formal content, such as illusory space, people and objects), it runs the risk of alienating a vast portion of ones audience. It's entirely conceivable that Malevich's painting, White on White, was received with cool indifference until his viewers learned more about Suprematism. Even then - with a well-written statement, a descriptive title and more - some people will never be fans of non-objective and hyper-abstracted artworks, simply because they're indifferent to the few properties or characteristics that remain in a work after the artist pulls away nearly everything (including one or more of the work's formal elements). So, what's an artist to do, especially if she values the structure and clarity that abstraction can bring to an artwork (with the exception of those crazy Cubists, of course)?

Meta-Aesthetics

"Sensual is everything that refers to the delight of the senses. And that's what artists do, is stimulate the senses in any possible way." - Shakira

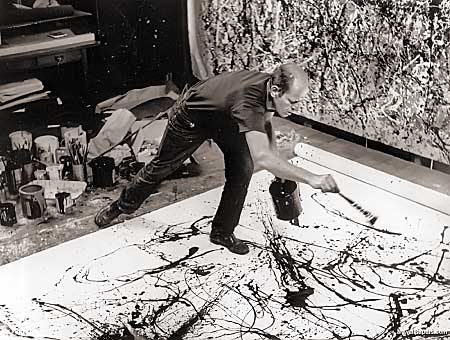

When medium-specificity directs creativity, the act of painting can become something more than simply laying pigments down on a flat surface with a hairy stick; it can also be about exploring the viscosity of paint and the effects of gravity and air-resistance as the paint is dripped and dribbled onto a canvas while it lays flat on the floor. Jackson Pollock explored these phenomena, to a great extent, when he created his "action paintings".

When painting becomes an action instead of an object, then the PROCESS of applying paint to a surface takes on an importance well-beyond anything that might have been attributed to a classical artwork, with its naturalistic imagery and illusory pictorial space. Instead of alienating his viewers, Pollock's daring break with tradition succeeded in attracting millions of new admirers and willing patrons.

The desire to experiment with materials and process seems to go hand-in-hand with abstraction and non-objective art. In a manner of speaking, the artist renounces the traditional depiction of physical reality and, instead, focuses on a "meta-aesthetic" exploration of her chosen medium. (The term meta-aesthetic, like metaphysical, denotes an experience that might begin with the physical, but quickly moves into a less-tangible realm of experience: one that's only accessible under certain conditions, like the way that wet paint fell from Pollock's brush and moved through space; a moment of entropy that's recorded on canvas for everyone to see and enjoy, but was only experienced in its true fullness by Pollock himself.)

Painting, in its traditional form, has a unique set of aesthetics that arise from the materials and the tools. Most, if not all painters will discover the joy of using a brush to lay down viscous paints; watching as the paint builds on a surface, gradually transforming emptiness with lines, textures and shapes of vibrant and muted colours; feeling countless varieties of resistance as the paintbrush is pulled through wet layers; smelling the subtle (and often not-so-subtle) fragrance of oils or acrylics rising from the painting's surface; watching in amazement as each brush stroke adds another note toward completion of a visual symphony filled with melody, point, counterpoint, rhythm, discord, harmony, tone and tempo. Painting fills the senses and envelops the painter in a world like no other. It's a meta-experience that all painters will share, but is not accessible to the viewer.

Of course, different art-making processes — carving marble, throwing clay vessels, drawing with graphite on paper, making lithographic prints, welding steel forms, etc. — each have their own, unique meta-aesthetic appeal. This often becomes an important part of the creative experience for an artist, even-though it's nearly impossible to convey such things to the viewer. At times, these sensual aspects of art-making will endear a particular process or a material to an artist, making repetition of one particular type of work desirable and even irresistible. It's more akin to managing an addiction, rather than the common misconception that "endless repetition equals a lack of new ideas".

Spirituality to Minimalism

"Minimalism had to be born, not out of a mere spur-of-the-moment idea or yearning for a new lifestyle, but from an earnest desire and fervent need to rethink our lives." - Fumio Sasaki

When formal and material concerns supplant mimesis, naturalism must be discarded in favour of a new universe: one that teems with abstract and non-objective shapes, colours, line and texture. Paul Klee, among others, found tremendous inspiration in this new realm, producing works that continue to challenge and delight viewers, decades later.

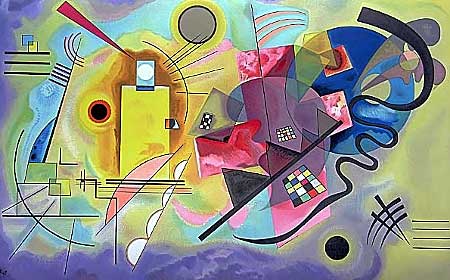

In the early part of the twentieth century, Wassily Kandinsky and other artists explored this new "universe of pure form", presenting the world with some of the first, truly non-objective artworks. Kandinsky teamed up with a group of Russian and German painters to form a group called, Der Blaue Reiter (the Blue Rider). These intrepid artists can rightly be called, the "fathers of modern abstraction".

A fascinating aspect of Kandinsky's art is its connection to spirituality. Dissatisfied with mainstream religion, Kandinsky and a surprizing number of his peers joined the Theosophical Society. Theosophy was co-founded by a charismatic Russian lady named Helena Blavatsky who claimed that she could communicate with the dead. Although some have accused her of being a charlatan and staging paranormal phenomena during séances, Madame Blavatsky wrote copious essays about the spiritual significance of certain kinds of visual images and colours.

Blavatsky almost certainly inspired Kandinsky to write his book titled, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, in which Kandinsky described the phenomenal world as being comprised of "vibrations", like music. Kandinsky believed that this "vibrational dimension" of reality exists just below the surface of EVERYTHING; providing structure and harmony to the physical world and to life itself. According to Kandinsky, non-objective imagery is uniquely suited (by virtue of its non-descriptive character and aesthetic appeal) as a means of glimpsing this hidden dimension.

As an aside, there's a branch of physics that postulates that everything at the smallest scale imaginable (the Plank length) is comprised of vibrating strings (or loops). According to String Theory, different vibrations give rise to different forms of matter and energy, ultimately creating reality as we know it. In turn, String Theory and Loop Quantum Gravity are both subsumed by an even more abstracted notion of reality as arising from a membrane-like structure within a much, MUCH larger "loaf-like" conglomeration of "alternate slices" of reality (see M-Theory to learn more about this fascinating subject). It's currently beyond the limits of our technology to test this hypothesis; nevertheless, it's a beautiful example of how Art and Science sometimes converge.

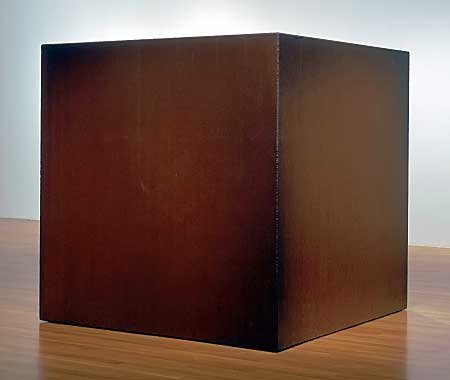

Ultimately, as artists became more sophisticated about abstraction and non-objectivity, movements such as Minimalism were born. Arising in the 1960's and coming to fruition in the 1970's, Minimalism is the hyper-abstraction of not only individual features from a subject, but also its formal elements. Anything that seemed the least bit ornamental was mercilessly excised, resulting in stark, pristine surfaces and spartan volumes that have been simplified to a breath-taking degree. For the sculptors at this time, geometric shapes and volumes became the preferred choice for subject matter, perhaps because geometry doesn't need abstraction (as mentioned earlier, geometric forms already reside in a Platonic universe of ideas). One of the most celebrated practitioners of Minimalism was Tony Smith (Kiki Smith's father!).

Descriptive & Post-Facto Titles

"For me, titles are either a natural two-second experience or stressful enough to give you an ulcer." - Sloane Crosley

The flattening of pictorial space, simplification of forms and generalization of features are all hallmarks of abstraction. The application of this process, when taken to its extreme, results in the creation of a nearly non-objective artwork. Here we discover an uncomfortable truth about making abstract artworks: namely, the artist must be sensitive enough to recognize that moment when only the most vitally-important characteristic of her subject remains.

In other words, she must be aware that if she pulls away one more feature, the work may lose its connection to the original subject and fall into the world of non-objective forms. When that happens (and it sometimes does), all is not lost if the artist provides a clue, such as a descriptive title (like, Crying Muse). I've experienced this phenomenon with several of my own sculptures: hyper-abstracting a subject to such a degree, that viewers misconstrue the work as having no analogue in the physical world (see the final image in this essay).

In the end, a descriptive title may be the best way to embed even the most severe abstractions within a familiar context, thereby providing the viewer with a "conceptual peg" on which to hang the artwork. If it's a non-objective artwork (with no analogue in the physical world), then the contextual hook may need to be something very familiar, such as Tony Smith's sculpture, Die. Did Smith name his sculpture after the six-sided cube that we use to play games or, did he chose this word because it's the verb for death? (Click here to learn more about, Die.) I think it's unlikely that Smith was inspired by dice or by death. It's far more probable that he chose this exceedingly simple form for no other reason than wanting to make the simplest form that he could envision. He did his research (made a maquette; found an industrial manufacturer; provided them with the specifications) and then named the sculpture AFTER the work was completed.

For the artist, a post-facto title becomes an exercise in trying to anchor a non-objective artwork to something that's relatable for the viewer. As the artwork becomes more complex and esoteric (e.g., an artwork about the negative space that surrounds a biomorphic, 3-D volume), it becomes progressively more difficult (but not impossible) to come up with a title that's both descriptive AND familiar. Did I choose the title, The Kiss because that sculpture reminded me, post-facto, of embracing lovers? I was certainly aware of the sculptures of Rodin and Brancusi. Or, did I hyper-abstract that subject from the very start? Does it matter?

Perhaps Marcel Duchamp — prankster, iconoclast, founder of Dada, a father of Modern Art and adherent to the belief that concepts are as important to an artwork as any of its other properties — was very wise when he cautioned against making art that consists of nothing more than the "tasteful arrangement" of formal elements. In an essay that he wrote in 1957, Duchamp suggested that "... art-making has to be based on other terms than those of arbitrary, formalistic, tasteful arrangements of static forms." (Click this link to hear Duchamp read an excerpt from his essay, The Creative Act.)

Further Research

I would recommend these excellent videos about art:

- The Case for Abstraction (Art Assignment, Season 3 Episode 7 | 9m 17s)

- I Could Do That (Art Assignment, Season 2 Episode 14 | 5m 40s)

- The Case for Minimalism (Art Assignment, Season 2 Episode 41 | 4m 36s)

- The Rules Of Abstraction With Matthew Collings, 2014 (Art Documentaries | 15m 00s)